Death is perceivable in different ways throughout the show, first there’s the tradition of the vanitas which is explored by Alexandre James. Vanitas which comes from the latin vanus and which means ‘empty’ acts as a reminder of our own mortality, of the fragility and beauty of life, traditionally illustrated by skull and/or flowers. More specifically here, it might also point at the death of the artist and her/his attempt to transcend her/his own mortality with art. It is worth pointing out that Alexander James very much anticipates the becoming of his work beyond his own life and prepares his own legacy by archiving and documenting his practice extensively. His photographs also seem to investigate the mortality of his medium (i.e. 1930s analogue photography) by transcending it with the reflecting qualities of water. Somehow, he is challenging the cultural and economical pressures that qualifies a medium as dead. The tour de force of his approach is to use the reverberating and transparent quality of light, which frames and beautifies the props photographed, rather than a blinding white light that saturates the lens. To me, the drowning of objects in Vanitas (2012) is paradoxically generative of images. The death of the props gives birth to the work of art. One is witnessing a process of metamorphosis where water is simultaneously death and life. Thus, water is not only contradictory but it is also essentially transient. In L’eau et Les Reves (Water and Dreams, 1942) French philosopher Bachelard explains that one never swims in the same water, that swimming is always a discovery, a form of christening always anew. Yet, the act of photographing suspends the transient quality of water to reveal its materiality. The materiality of water is, according to Bachelard, what enables the dream to happen. Indeed, he explains that in order to dream one has to dream through matter rather than objects. It is as if, Alexander James in Resting in a Bed of Dreams (2012) is illustrating that point, he immerses his work into the physiological qualities of water in order to open up an oneiric experience for the viewer.

Vanitas also acts as a plea for humility in the face of the transcendence. Interestingly, Bachelard reminds us that inherently water can be associated with pride as the myth of Narcissus illustrates it. Consequently, there’s a duality of water, at the same time transparent, and even comparable to a lens in James’ pieces, it is also a mirror in which one is absorbs by her/his own image. In James’ work water could be thought of as a mirror reflecting the history of art, from the Old Master to the Pre-Raphaelites, that the artist is referring to. The nexus of death and time can also be synonymous with a pause in the creative process. For instance, it is worth noticing that the term ‘dead water’ is a technical nautical term that describes two layers of water of different salt densities which forces a ship to slow down. This physical phenomenon evokes to me the idea of being caught by your own medium and to somehow never being able to tame it. In other words, it seems to imply being in resistance with your medium. In Alexander James’ work, the act of photography suspends the passing of time inherent in the substance of water and as such begins an engagement with the medium of water that takes the form of an intervention.

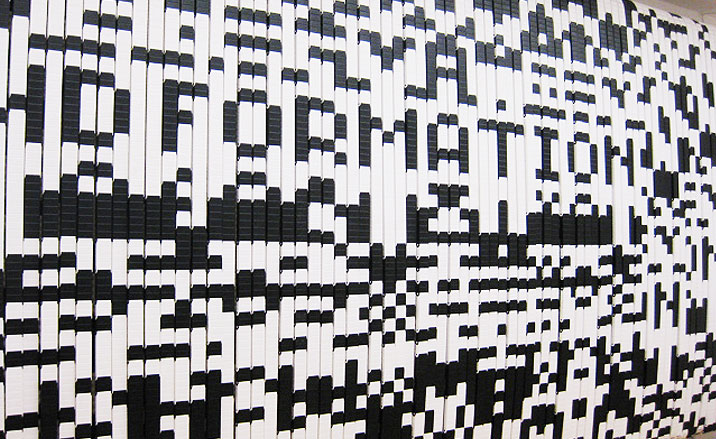

In Gail Olding’s sculptures death is palpable in a different manner. Razzle Dazzle, a large golden bullet which denounces the glamorisation of war found in literature and more specifically in religious texts, embodies death to be; it is the threat of death that is deployed before our eyes. Razzle Dazzle is a powerful and mysterious object, it radiates its enigmatic yet provocative presence to the space. It could be red as a totem, in as much as, it is a piece that conveys different meanings coming from different groups all part of the same society. Indeed, the term also refers to the cubist-inspired camouflage paint that war ships were using during WWII. Simultaneously phallic and synonymous of an advanced medical remedy, golden bullet also promises to offer an effective solution to a previously unsolvable problem. Like a totem on which aspirations and identities are projected on, fragments of significance are thrown onto the smooth surface of the bullet, creating a conceptual artefact which, at the same time, belongs to contemporary culture and yet keeps its elusiveness by refusing to be labeled in one way or another.

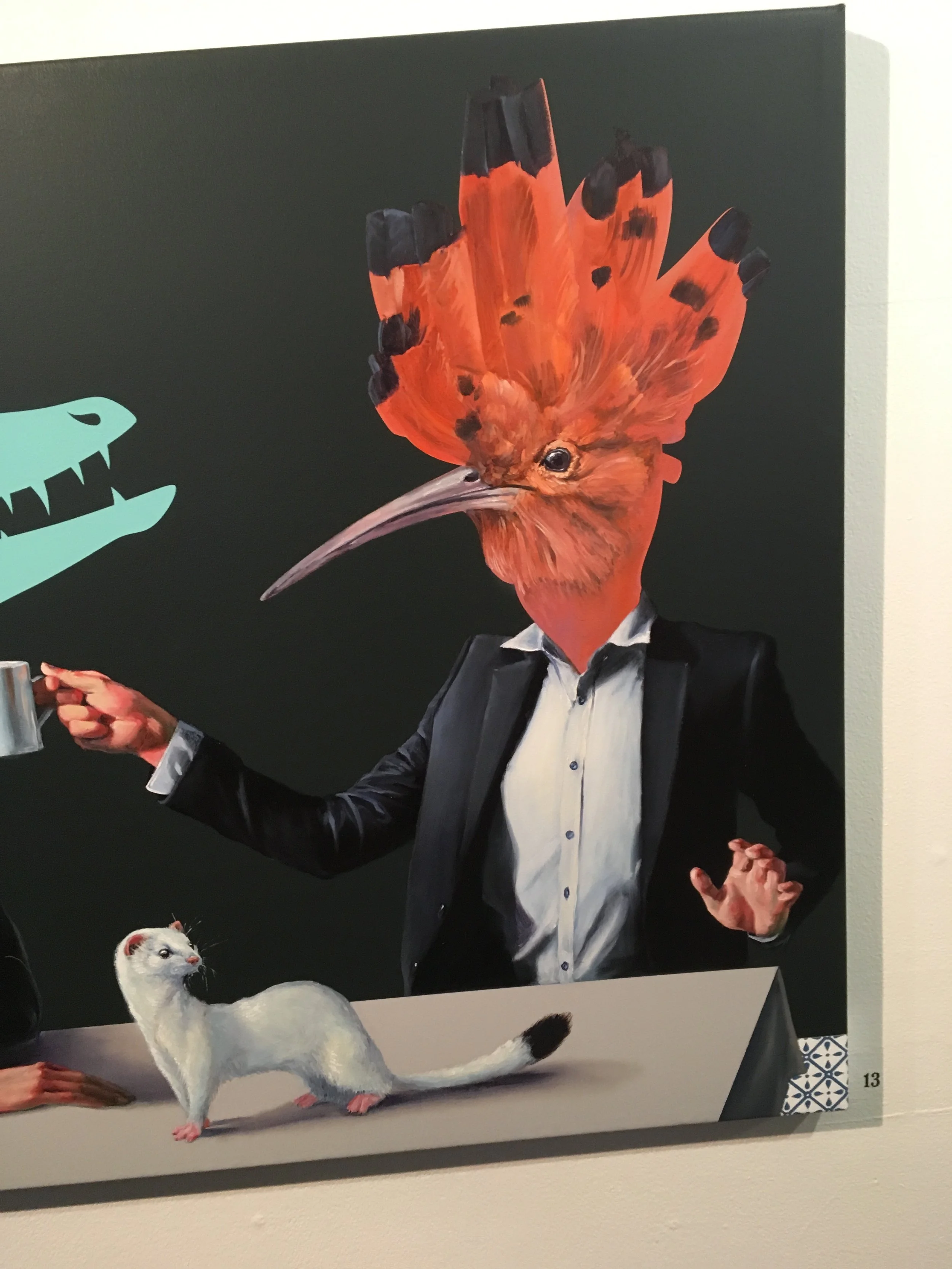

If in Alexander James’ Vanitas the objects are a mean to set up a visual narrative in which objects are vehicles of an attempt to reach the transcendence, to touch upon the metaphysical, whereas in Coffield’s painting the objects are a mean of expressing what the world means to him. This is where the heritage of 18th century French painter Chardin is the most perceivable. In a recent programme The Art of France, Art Historian Andrew Graham Dixon explains that Diderot celebrated Chardin for his ability to convey, for instance in the painting The Skate (1728), emotions and ideas closer to a simpler life and therefore closer to truth. Whereas, Diderot condemns Boucher for representing the decadent life of the ruling class. The philosopher is turning art criticism into social criticism where the value of the work of art is connected to its capacity to nurture a connection with truth or not. Following up Diderot’s analysis, Graham Dixon see in Chardin a very political and revolutionary work.

If the artists curated here are influenced by literature - Hamlet for Alexander James, T.S.

Eliot for Gail Olding and Marcel Proust for Darren Coffield - the relationship between text and image manifests itself in very different ways in each practice. If Alexander James is embracing the language and codes of the vanitas and its presence in art history, Darren Coffield is re-intepretating the language of the nature morte and the heritage of Chardin and Cezanne, Gail Olding’s practice stands out in that both Each Day and Razzle Dazzle are operating outside the field of languages and distribute instead, in the gallery space, a few signs flexible enough in their conceptual architectures to allow us the appropriate them and to truly engage in a conversation with the artist.

![Screenshot-2018-5-1 Ocean Liner Design History on Instagram “Wonders I discovered thanks to the #oceanliners exhibition vam[...].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57e54e7aebbd1adb123e12e4/1525208833749-5LH0A2PXS4YX773MR4N3/Screenshot-2018-5-1+Ocean+Liner+Design+History+on+Instagram+%E2%80%9CWonders+I+discovered+thanks+to+the+%23oceanliners+exhibition+vam%5B...%5D.png)

![Screenshot-2018-5-1 Ocean Liner Design History on Instagram “An adorable chair coming from the First Class children’s playr[...].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57e54e7aebbd1adb123e12e4/1525209280376-V1Y40ZKXW1T7VY0QRXGQ/Screenshot-2018-5-1+Ocean+Liner+Design+History+on+Instagram+%E2%80%9CAn+adorable+chair+coming+from+the+First+Class+children%E2%80%99s+playr%5B...%5D.jpg)