The Crystal Land exhibition at the White Cube brings together works developed between 2008 and 2017 by American artist Josiah McElheny. The titled of the show is borrowed from a Robert Smithson’s essay for Harpers Bazaar published in 1966 in which the artist recalls a visit to the Watchung Mountains with Minimalist artist Donald Judd. The show is divided into three distinct parts, each revolves around a character and aims at exploring the multi-facetted concept of modernism by asking: what alternative historiographies can be imagined?

Josiah McElheny The Crystal Land at the White Cube, a gallery view.

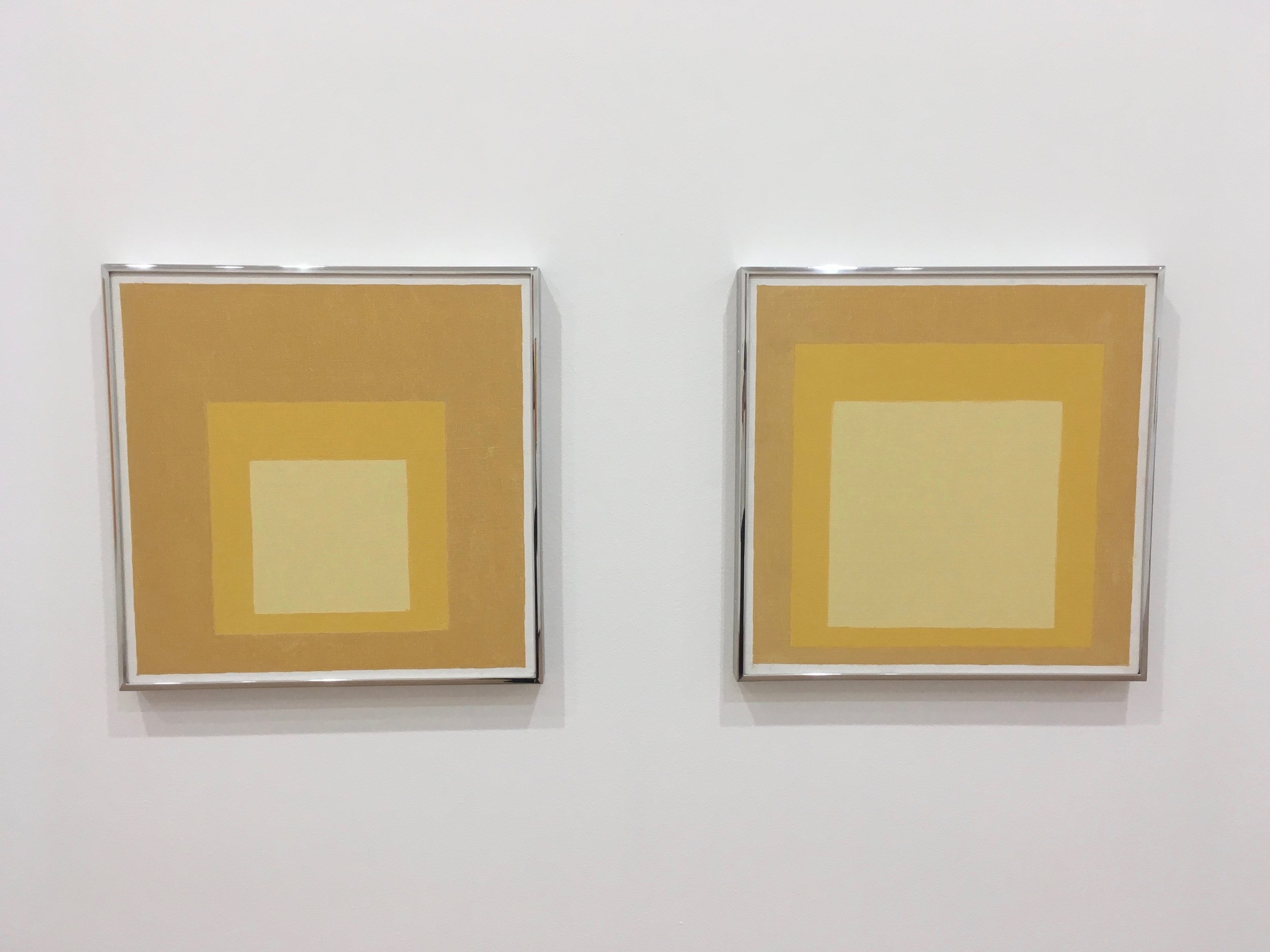

The first part of the exhibition is engaged in a dialogue with Simthson’s The Crystal Land essay and refers to works such as, Three Mirror Vortex (1965) or Mirrored Ziggurat (1966). By evoking these mirrored pieces McElheny seems to examine Smithson’s exploration of modernism. More specifically, in the 1960s, with his reflective surfaces installations, Smithson could be seen as extending some of the precepts of cubism; as they can be found for instance in Picasso Table in a Cafe (1912). In this radical painting Picasso provides the viewer with the multiple perspectives of a perceived object on the 2D surface of the canvas. McElheny takes part in Smithson's conversation with cubism by creating structures which translate, in 3D, the multiple broken-down and then re-assembled viewpoints contained in modernism. Interestingly, the connection with modernism is apparent in the way McElheny chooses to describe his work as paintings, which therefore explicitly inscribes his practice in an art historical perspective.

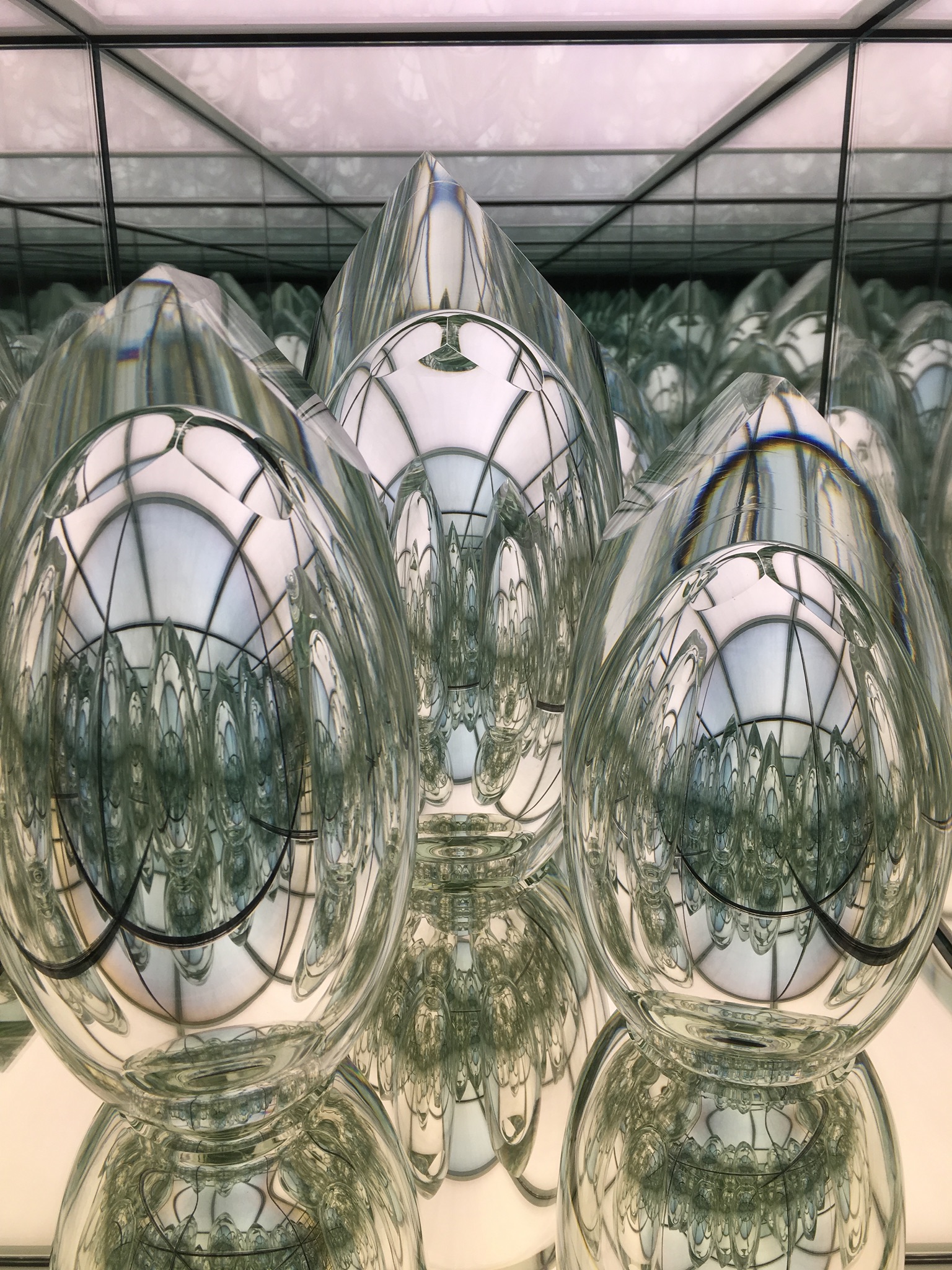

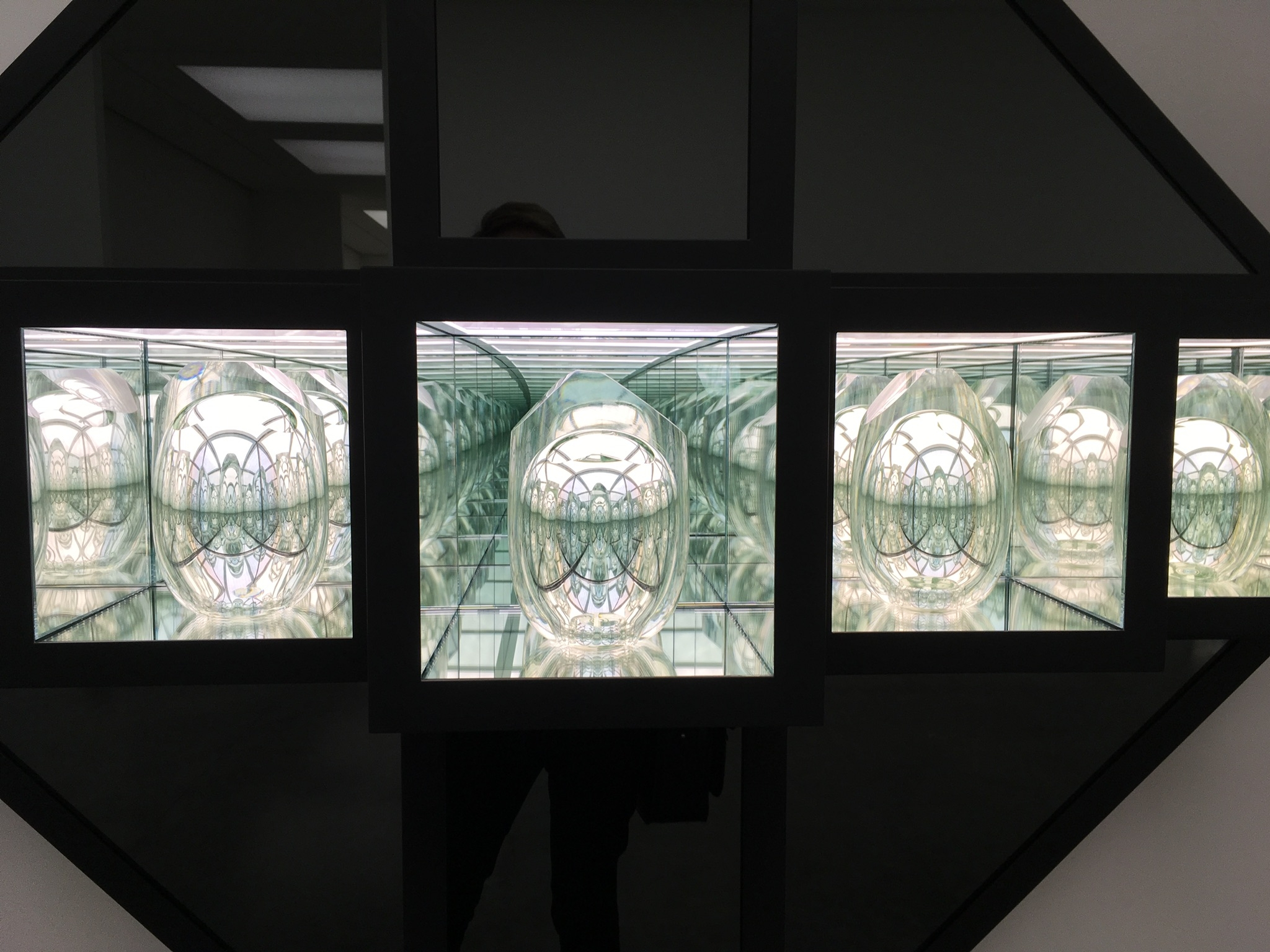

The result is a series of protruding geometric structures comprised of mirrored interior chambers in which are placed hand-blown ovoid glass objects. With their polished surfaces those enigmatic objects distort the structural lines of the box that contains them and generate a series of black and white abstract images. Besides, the contrast between the outer powder-coated steel surfaces of the paintings and their interior mirrored chambers reinforces the optical illusions that de-multiply the glass objects. The fact that McElheny’s pieces seem to erupt from the gallery walls enables the viewer to observe the work from different angles and, somehow, echoes Smithson’s intent to transcribe the multiple perspectives of cubism into a physical experience.

As a result, there seems to be a mise en abîme in the works presented here, not only from a visual point of view (The Crystal Landscape Paintings physically jut out into the gallery space and yet visually offer a recessed perspective disappearing into the wall) but also from a conceptual point of view, inasmuch as Robert Smithson’s exploration of modernist medium specificity is here feeding McElheny’s examination of historiography.

The third chapter of the show presents the conclusion of a collaboration between Josiah McElheny and astronomer David H. Weinberg in a set of suspended, chrome-plated aluminium sculptures entitled Island Universe (2008). The sculptures, in the shape of constellations, are the result of a four year investigation into the origins of the universe and represent an accurate data visualisation of the Big Bang.

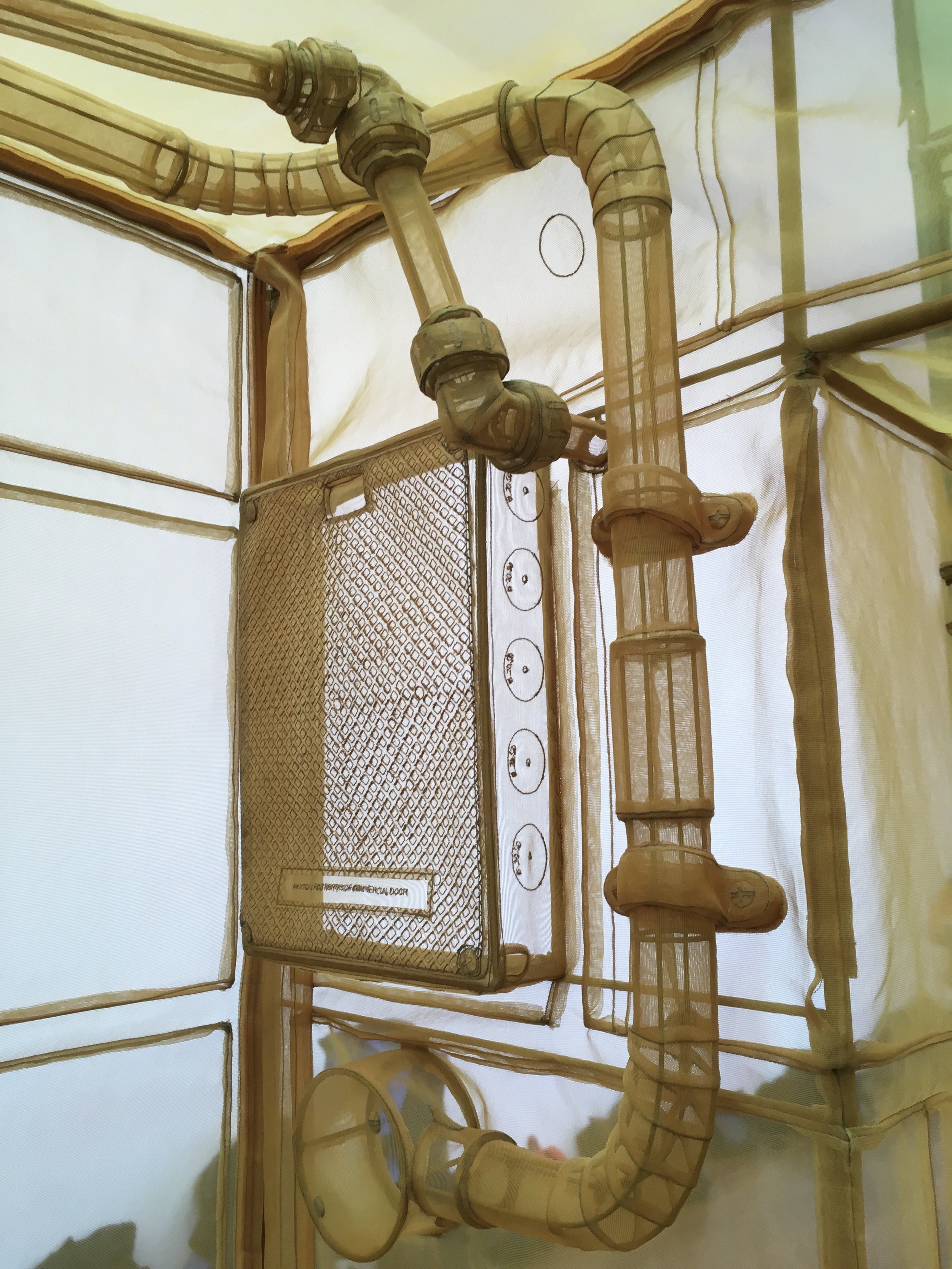

The work exhibited in the second part of the exhibition, titled The Light Club of Vizcaya: a Women’s Picture (2012), caught my attention the most. The film is an essay of gender studies, a piece of poetry and an open-ended documentary which weaves together the lives of fictional and real characters. McElheny took his inspiration from a short novel by German author Paul Scheerbart titled Light Club of Batavia: A Ladies’ Novelette (1912). The book is a fantastic tale which portrays a group of socialite women who meet in a hotel in Jakarta and decide to build a spa entirely out of Tiffany glass so that they can ‘bathe in light’. It seemed to me that the projection room in which the film is shown, with its walls made of multicoloured glass bricks, evokes this utopian vision. The script of the film, written by Canadian poet Rachel Zolf, tweaks Scheebart’s story, and situates the plot in what is now Vizcaya Museum and Gardens on Biscayne Bay, Miami. Vizcaya, was built by Chicago industrialist James Deering and was his winter residence from 1916 until his death in 1925. The property which sits within 180 acres is an interpretation of Venetian architecture on a gigantic scale and is comparable to the castle folly built by publishing magnate Hearst in California (known for being the inspiration of Xanadou in Citizen Kane). Zolf chronicles the utopian project via the voice of a narrator whose great-grand aunt named Mattie Edwards, is an architecture photographer who documents the building of Vizcaya in 1910s. The script imagines a group of characters discussing and planning the construction of a Light Club made of glass underneath the mount built at Deering’s property. The 30 minutes film blends archive footage with contemporary shots of the house and seeks to unveil the contrasted sides of modernism by inquiring: is it possible not to use utopia as a blueprint but nonetheless keep it as a dream? The film simultaneously manages to paint a disenchanted picture of modernism by showing the ruins of Vizcaya - thereby symbolically pointing at the debris of the utopia it once incarnated- and still considering uptopia as a creative pathway. At one point in the documentary, the narrator states that the utopia of the Light Club offers a space for ideas to be turned into images. To me, this statement acts as a reminder for the viewer of the potential of film as a medium. As such, before entering the projection room, the curating of this part of the exhibition places a series of posters where the language of utopia is explored in typographical terms, as a way of announcing that the viewer is about to enter a space where ideas are going to be turned into images before her/his eyes and where historiography is about to be re-invented as a visual language. The posters also remind me of the dramatisation at play in cinema theatres and the sense of anticipation they can instil into the viewer's mind.

As I'm watching the film, I am wondering, here and there with the narrator, if the Light Club of Vizcaya exists. Then, I realise that the Light Club almost ceases to be an architectural project and becomes an elusive protagonist of the film about whom I am searching clues and traces in order to reconstruct my own understanding of the story. It is noteworthy that despite the mise en abîme of viewpoints at play in The Light Club of Vizcaya (an early German 20th century novel adapted by a contemporary poet, told through the fictional voice of a narrator whose observations are based on the memorabilia of a distant relative, shot and edited by Josiah McElheny) the film leaves room for the viewer to participate, from an imaginary point of view, in the documentary. Indeed, the fact that the work uses, in its narrative structure, visual metonymies such as a crystal carafe, a chandelier, or the detail of a column, to me, plays a part in the openness and receptiveness of the work As such, in The Light Club of Vizcaya, the notion of utopia appears revisited from various perspectives -a little bit like in a Robert Smithson’s mirrored installation- and even somehow partly revived to become not solely a collective alternative vision of reality but an imaginary gateway for the individual to rethink what constitutes reality.

A view of the ovoid glass objects placed in McElheny's paintings.

Detail of one of Josiah McElheny's paintings.

One of Josiah McElheny's The Crystal Landscape Paintings, 2017.

A view of the projection room where The Light Club of Vizcaya: a Women’s Picture (2012) is shown.

The Light Club of Vizcaya 100th anniversary poster, designed by Josiah McElheny and Conny Purtill, silk screenprint, limited edition of 100.